Freediving Deaths: Causes, Prevention & What We Can Learn

A comprehensive examination of freediving fatalities, the physiological mechanisms behind them, and evidence-based strategies to keep yourself safe in the water.

Introduction: Confronting an Uncomfortable Truth

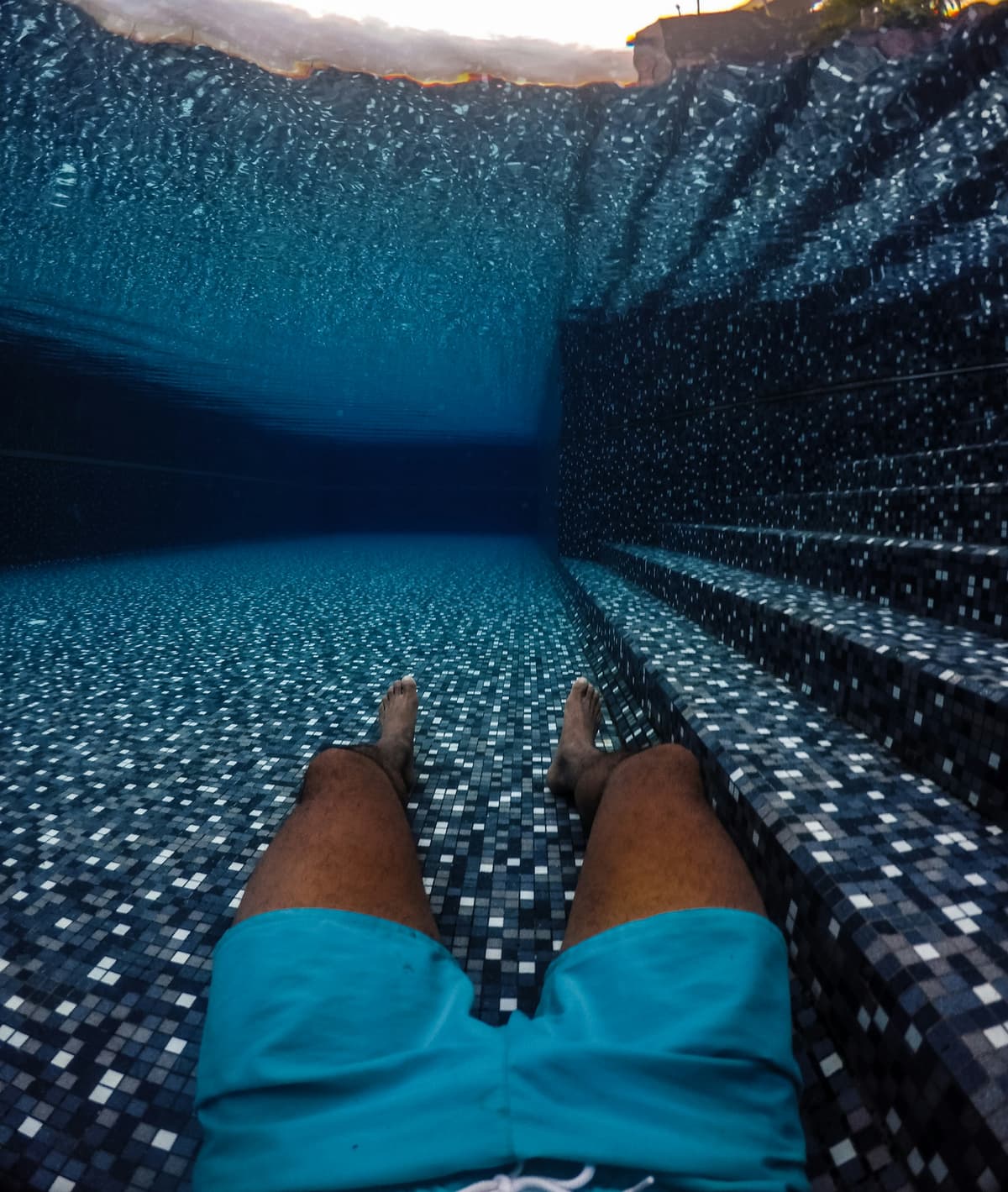

Freediving is one of the most rewarding activities you can pursue. The sensation of descending into the blue on a single breath, the meditative stillness, the connection with the underwater world—it's transformative. But we'd be doing you a disservice if we pretended it came without serious risks.

This article isn't meant to scare you away from freediving. It's meant to help you understand exactly what can go wrong, why it happens, and—most importantly—how to prevent it. Because the uncomfortable truth is that most freediving deaths are preventable. They happen not because freediving is inherently deadly, but because people didn't understand the risks or didn't follow basic safety protocols.

We're going to examine real statistics, real case studies, and the real physiological mechanisms that kill freedivers. Some of this will be difficult to read. But if this information saves even one life, it's worth the discomfort.

The Numbers: How Many Freedivers Die Each Year?

Getting accurate freediving death statistics is surprisingly difficult. There's no mandatory reporting system, deaths are often misclassified as "drowning," and the line between recreational snorkeling and freediving is blurry. That said, we can piece together a reasonably clear picture from available data.

What the Data Shows

According to Divers Alert Network (DAN) data covering 2004-2017, approximately 995 breath-holding incidents were recorded, with a 73% fatality rate—meaning roughly 727 deaths over 13 years, or about 56 per year in reported incidents alone. However, this figure almost certainly underestimates the true global number.

James Nestor, author of Deep, estimates that of the approximately 10,000 active freedivers in the United States, about 20 die each year—a rate of roughly 1 in 500. To put this in perspective:

BASE jumping: approximately 1 in 60

Firefighting: approximately 1 in 45,000

Mountain climbing: approximately 1 in 1,000,000

Perhaps the most sobering statistic: of freediving accident cases analyzed by DAN, approximately 73% were fatal. This means that if something goes wrong underwater, you have less than a one-in-three chance of survival. The margin for error is razor-thin.

Who Dies?

DAN data reveals clear demographic patterns:

Males account for approximately 80-90% of fatalities across all age groups

The highest incident rate occurs in males aged 20-29 years old

However, fatalities are more common in divers over 40, likely due to underlying cardiovascular conditions

Approximately 90% of reported freediving deaths occur in the ocean (vs. pools or other bodies of water)

Competitive vs. Recreational: A Stark Contrast

Here's something that might surprise you: competitive freediving is dramatically safer than recreational freediving or spearfishing.

In more than 50,000 competitive dives supervised by AIDA, there has been only one competition fatality—Nicholas Mevoli in 2013. That's a death rate of roughly 1 in 50,000 competitive dives, compared to roughly 1 in 500 for recreational freedivers annually.

Why the 100x difference? Competitive freediving has:

Strict safety protocols enforced by governing bodies

Mandatory trained safety divers (4-5 per athlete)

Medical personnel on standby

Athletes who understand their limits and train specifically for announced depths

Proper equipment including lanyards, lines, and buoys

Recreational freediving—especially spearfishing—often has none of these safeguards.

Primary Causes of Freediving Deaths

1. Shallow Water Blackout (Hypoxic Blackout)

This is the number one killer of freedivers, and it's also the most misunderstood. Shallow water blackout is estimated to be responsible for up to 20% of all drowning deaths worldwide—approximately 28,000 deaths annually.

How It Happens

Your body relies on carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels—not oxygen levels—to trigger the urge to breathe. When you hyperventilate before a dive (taking multiple rapid, deep breaths), you blow off CO₂ from your blood. This doesn't increase your oxygen stores significantly, but it dramatically suppresses your urge to breathe.

The result: you can hold your breath longer than your oxygen stores actually support. As you ascend from depth, the partial pressure of oxygen in your lungs drops rapidly due to decreasing ambient pressure. Your brain, suddenly starved of oxygen, simply shuts down—without warning. One moment you're swimming; the next, you're unconscious.

Warning Signs

There often aren't any. That's what makes this so dangerous. However, some divers report:

Tunnel vision or "graying out"

Tingling in extremities

A sense of euphoria or detachment

Loss of motor control ("samba" or LMC)

Involuntary twitching or jerking movements

By the time you notice these symptoms, you may have only seconds before losing consciousness. Many victims report feeling completely fine right up until they blacked out.

Why It's So Deadly

Unlike a typical drowning, where victims struggle and splash, shallow water blackout victims simply go limp and sink silently. They don't thrash. They don't call for help. They're often found motionless at the bottom of pools or the ocean floor.

Brain damage can begin within 2-2.5 minutes—significantly faster than in typical drowning cases because the diver was already severely oxygen-depleted when they lost consciousness.

2. Loss of Motor Control (LMC) / "Samba"

LMC is sometimes called a "near blackout" and is perhaps more dangerous than a full blackout. During LMC, the freediver is attempting to breathe but due to severe hypoxia cannot fully control their motor functions. They may exhibit:

Involuntary shaking or twitching

Erratic movements

Inability to keep their airway clear

Confusion or disorientation

The critical difference: during LMC, the protective laryngospasm reflex is not present. The diver's ability to control their own airway is severely compromised, making water aspiration very likely without immediate buddy intervention.

Any LMC event means the diving session is over. The diver should not return to the water for at least 24 hours.

3. Lung Squeeze (Pulmonary Barotrauma)

As freedivers descend, increasing water pressure compresses their lungs. Below a certain depth—typically 30-45 meters for most divers—the lungs can be compressed beyond their "residual volume." When this happens, negative pressure can cause fluid or blood to be pulled into the lung tissue.

A 2023 DAN survey found that approximately 80% of experienced competitive freedivers have suffered at least one lung squeeze, and 18% report having had 10 or more.

Symptoms of Lung Squeeze

Coughing (with or without blood)

Blood-tinged sputum or mucus production

Chest tightness or pain

Shortness of breath

Fatigue and lightheadedness

4. Cardiac Events

DAN data consistently shows that cardiovascular disease is present in a significant percentage of diving fatalities, particularly among older divers. The combination of breath-holding, cold water immersion, physical exertion, and the mammalian dive reflex places significant stress on the cardiovascular system.

Why Freediving Stresses the Heart

The Mammalian Dive Reflex causes bradycardia (slowed heart rate) when cold water contacts the face

Physical exertion from swimming increases oxygen demand while heart rate is suppressed

Cold water immersion can trigger cardiac arrhythmias in susceptible individuals

Breath-holding activates the sympathetic nervous system

5. Equipment and Environmental Factors

Other contributing factors to freediving deaths include:

Entanglement: Getting tangled in fishing lines, kelp, or float lines

Overweighting: Wearing too much lead, causing rapid sinking when consciousness is lost

Strong currents: Being swept away from safety or exhausted fighting currents

Cold water and thermoclines: Sudden temperature drops can cause shock response

Snorkel in mouth during dive: Acts as a direct conduit for water to enter the lungs if diver blacks out

Learning from Tragedy: Notable Freediving Deaths

Examining specific cases—while deeply sad—provides crucial lessons. These aren't sensationalized stories; they're learning opportunities that have shaped modern freediving safety protocols.

Nicholas Mevoli (2013)

Nicholas Mevoli was a 32-year-old American freediver who became the sport's first and only competition fatality at an international event. At Vertical Blue in the Bahamas, Mevoli attempted a 72-meter constant weight no-fins dive.

What Happened:

Two days earlier, Mevoli had suffered a lung squeeze and had been coughing up blood

Despite this warning sign, he proceeded with his CNF attempt

He surfaced after 3 minutes 38 seconds, signaled "okay," even posed for photos

Seconds later, he lost consciousness and fell backward into the water

Despite 90 minutes of resuscitation efforts, he died from pulmonary edema

Key Lessons:

Never dive after experiencing a squeeze. Coughing up blood is a serious warning sign that requires rest, not another dive attempt.

The pressure to compete or set records should never override physical safety signals

Athletes must report symptoms to medical staff

Natalia Molchanova (2015)

Natalia Molchanova is widely considered the greatest female freediver in history, holding 41 world records and 23 world championship titles. She could hold her breath for over 9 minutes and dive to 101 meters.

What Happened:

On August 2, 2015, the 53-year-old Molchanova was giving a private freediving lesson near Formentera, Spain

She made what should have been a routine 35-meter dive—well within her capabilities

She never resurfaced

Despite extensive searches, her body was never recovered

Key Lessons:

Experience and world records don't make you immune to danger

Molchanova was diving without a trained safety buddy at her level

Even "easy" dives require proper safety protocols

Stephen Keenan (2017)

Stephen Keenan was considered the world's most accomplished safety diver—the "guardian angel" of competitive freediving.

What Happened:

At Egypt's Blue Hole, Keenan was providing safety for Italian freediver Alessia Zecchini

When Zecchini became disoriented at depth, Keenan bolted to her rescue from approximately 50 meters

He successfully finned her to the surface—Zecchini survived unharmed

Keenan blacked out during or shortly after the rescue

He was found floating face-down and could not be revived

Key Lessons:

This was the first recorded death of a safety diver in action in freediving history

Safety divers push themselves to extreme limits during rescues

The question arose: "Who watches the safety divers?"

Audrey Mestre (2002)

Audrey Mestre was a 28-year-old French freediver attempting to break the women's No Limits world record—171 meters (561 feet).

What Happened:

Mestre reached her target depth of 171 meters

When she tried to inflate her lift bag for ascent, it failed—the air tank was nearly empty

It took nine minutes to bring her to the surface

She had a pulse when she arrived but could not be revived

Key Lessons:

Equipment must be meticulously checked and verified by multiple people

Safety protocols exist for a reason—never cut corners

Having a qualified medical team on standby is essential for deep diving

How to Protect Yourself: Evidence-Based Prevention

The good news: the vast majority of freediving deaths are preventable. Here's what the evidence tells us about staying safe.

The Cardinal Rule: Never Freedive Alone

This isn't a suggestion—it's the single most important safety rule in freediving. DAN data shows that the majority of recreational freediving fatalities involve divers who were alone or had separated from their buddy.

Having a trained buddy watching you is your only defense against shallow water blackout. You cannot rescue yourself from a blackout—by definition, you're unconscious.

Critical Points:

An untrained buddy is almost as bad as no buddy. Your buddy needs to know how to recognize hypoxia, perform a rescue, and administer rescue breaths.

The "one up, one down" rule means one person dives while the other's sole job is to watch.

For spearfishing, share one gun between two divers—this ensures one person is always watching.

Watch your buddy for at least 30 seconds after they surface—surface blackouts can occur after the diver appears fine.

The Rescue Protocol: Blow-Tap-Talk (BTT)

Every freediver should know how to rescue an unconscious buddy:

Retrieve: Quickly bring the diver to the surface, protecting their airway.

Support: Keep their face out of the water at all times.

Remove facial equipment: Take off their mask.

Blow-Tap-Talk: Blow sharply across their eyes and cheeks, tap gently on their cheek, talk to them firmly using their name.

If no response within 15-30 seconds: Begin rescue breaths.

If still no response: Get them out of the water and begin CPR.

Most blackout victims revive within 15 seconds of proper BTT technique. The key is getting their airway out of the water immediately.

Never Hyperventilate

Do not take multiple rapid, deep breaths before diving. This is the primary cause of shallow water blackout.

Proper freediving breath-up involves:

Slow, relaxed breathing

Focus on full exhalation rather than maximum inhalation

One final, full breath before descent—not 10 rapid ones

Get Proper Training

A significant number of freediving fatalities involve people with no formal training. A proper freediving course from a recognized agency (AIDA, PADI, SSI, Molchanovs, etc.) teaches you:

The physiology of breath-hold diving and why blackouts happen

Proper breathing techniques (without hyperventilation)

Rescue and buddy protocols (BTT technique, rescue scenarios)

Equalization techniques to prevent barotrauma

How to recognize danger signs in yourself and others

The competitive freediving statistics prove that proper training and safety protocols dramatically reduce fatality rates—from 1 in 500 to 1 in 50,000.

Proper Weighting

You should be positively buoyant (floating) at 10 meters and above. If you black out, positive buoyancy gives your buddy a chance to reach you before you sink too deep.

The Exhale Test: At the surface, exhale fully. If you sink, you're wearing too much weight.

Additional Safety Practices

Remove your snorkel before diving: If you black out with a snorkel in your mouth, it acts as a direct conduit for water to enter your lungs.

Use a lanyard and line: For depth diving, a lanyard attached to a dive line prevents you from sinking away if you black out.

Rest between dives: Rest at least twice the duration of your dive, and at least 5 minutes between deep dives.

Practice recovery breathing: After every dive, practice hook breathing to reoxygenate your blood quickly.

Know When to Stop

If you experience any of the following, your diving day is over:

Coughing up blood or blood-tinged sputum (sign of lung squeeze)

Loss of motor control (LMC/samba)

Blackout or near-blackout

Chest pain or difficulty breathing

Feeling cold, exhausted, or unwell

Difficulty equalizing

Any sense that something isn't right

No fish, no record, no photo is worth your life. There will always be another day to dive.

The Bottom Line: Respect the Water

Freediving can be practiced safely for a lifetime. The sport isn't inherently deadly—but it is inherently unforgiving of complacency and carelessness.

The Non-Negotiables

Never freedive alone — An untrained buddy is diving alone

Never hyperventilate — One full breath, not ten rapid ones

Get proper training — From a recognized certification agency

One up, one down — Your buddy's only job is watching you

Know your limits — Stay at 50-60% of your maximum capacity

Stop when something's wrong — No dive is worth your life

Remember

The difference between competitive freediving's 1-in-50,000 fatality rate and recreational freediving's 1-in-500 rate isn't luck—it's preparation, training, and safety protocols.

The best dive is one you come back from.

Resources

Emergency Contacts

DAN Emergency Hotline: +1-919-684-9111 (24-hour diving emergency assistance)

DAN Medical Information Line: +1-919-684-2948

Organizations and Training

Divers Alert Network (DAN): dan.org — Research, emergency services, and diving safety information

AIDA International: aidainternational.org — International freediving federation with safety standards

PADI Freediving: padi.com — Freediving certification courses

Molchanovs: molchanovs.com — Education and certification

Further Reading

DAN Annual Diving Reports: dan.org/research-reports

Deep by James Nestor — Exploration of the science and culture of freediving

One Breath by Adam Skolnick — The story of Nicholas Mevoli

This article is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for proper freediving instruction from a qualified instructor. Always get professional training before attempting breath-hold diving.

If you're new to freediving, please consider taking a certified course before diving in open water. If you've been diving without formal training, it's never too late to learn proper safety protocols. The life you save may be your own—or your buddy's.

Freediving Safety — Complete Series

- 1Is Freediving Dangerous? Risks, Statistics & How to Stay Safe

- 2Shallow Water Blackout: The Silent Killer in Freediving and Swimming

- 3Freediving Deaths: Causes, Prevention & What We Can Learn

- 4Freediving Safety: The Buddy System - Your Lifeline Underwater