Freediving Safety: The Buddy System - Your Lifeline Underwater

The buddy system isn't just a recommendation in freediving—it's the fundamental safety protocol that stands between life and death underwater. Yet despite its critical importance, many divers underestimate its necessity, and many instructors provide inadequate buddy system training, leaving students dangerously unprepared for real-world diving situations.

This guide covers everything you need to know: the statistics that prove why solo diving kills, how to be an effective safety diver, proper rescue procedures, and what to do when you can't find a buddy.

The Statistics: Why Solo Diving Is Lethal

The numbers are unambiguous. Solo diving—or diving with an inattentive buddy—is the single greatest predictor of whether a freediving accident becomes a fatality.

The Data on Solo Diving Deaths

40% of diving fatalities occur during buddy separation, with an additional 14% on planned solo dives (DAN Fatalities Workshop)

89.6% of snorkelling and freediving drowning victims lacked an effective buddy system

75% of freediving accidents are fatal — if something goes wrong, the odds are against you

In an Australian study of 317 snorkelling and breath-hold diving deaths (2000-2021), 32% of victims set out solo, and only 25% were with someone at the time of death

A Queensland study found that of breath-hold divers who died from extended apnoea, 17 had set out solo, 4 separated during the dive, and only 1 was still with their buddy

Why Competitive Freediving Is 100x Safer

The contrast between recreational and competitive freediving death rates tells you everything you need to know about the buddy system's effectiveness:

Recreational freediving death rate: approximately 1 in 500 dives

Competitive freediving death rate: approximately 1 in 50,000 dives

That's a 100-fold difference. In over 50,000 competitive freediving dives worldwide, there have been only two competition deaths (Audrey Mestre in 2002 and Nicholas Mevoli in 2013). After each tragedy, competition rules and safety regulations were strengthened.

The difference isn't that competitive freedivers are superhuman—it's that they always have trained safety divers watching them. Mandatory medical checks, strict protocols, and multiple safety divers at depth create an environment where blackouts are quickly rescued rather than becoming drownings.

The buddy system works. The statistics prove it.

Why Spearfishing Is Especially Dangerous

Spearfishers face disproportionately high fatality rates compared to recreational freedivers, and the reasons are largely preventable.

The Spearfishing Problem

Spearos dive alone more frequently, often due to difficulty finding a buddy or the belief that hunting is a solo activity

Target fixation leads to extended dives — when you're focused on landing a fish, you lose track of time and depth

Many spearos learn from YouTube and forums, skipping formal safety training entirely

Even when diving with a partner, spearfishers often separate by 30+ metres while hunting, negating the buddy system's protection

Shallow water blackout is the #1 cause of spearfishing deaths — far exceeding shark attacks, despite what movies suggest

The argument that "you can't watch your buddy and hunt at the same time" is precisely why proper spearfishing safety requires a dedicated surface watcher or boat-based spotter — not a buddy who's also hunting.

What Your Buddy Actually Does: The Physiology

Understanding why you need a buddy requires understanding what happens during a blackout — and why you cannot save yourself.

Blackout Happens Without Warning

Shallow water blackout (hypoxic blackout) typically occurs in the final 10 metres of ascent or at the surface. The diver often feels completely fine moments before losing consciousness. There is no struggle, no panic, no warning — just sudden, complete unconsciousness.

An unconscious diver underwater cannot save themselves. Without intervention, they will drown. It's that simple.

The Rescue Window

When blackout occurs, the timeline is brutally short:

10-15 seconds: Window to recognise the emergency

30-60 seconds: Window to initiate rescue and get the diver to the surface

2-3 minutes: Brain damage begins; beyond 4 minutes, it becomes permanent or fatal

During a blackout, the body enters a protective state. The larynx spasms shut (laryngospasm), preventing water from immediately entering the lungs. The heart continues beating. The diver is alive — but only for a brief window. Without rescue, laryngospasm eventually relaxes, terminal gasping occurs, and drowning follows.

Your buddy is the only thing standing between "brief blackout with full recovery" and "drowning."

LMC (Samba): More Dangerous Than Blackout

Loss of Motor Control (LMC), often called "samba" due to the involuntary twitching movements, is arguably more dangerous than full blackout.

During LMC:

The diver is conscious but cannot control their body

No protective reflexes are present — unlike blackout, there's no laryngospasm

The diver may attempt to breathe but cannot control their airway

Water aspiration is highly likely without immediate buddy intervention

LMC can progress to full blackout. A diver experiencing LMC at the surface needs their buddy to immediately support their head and keep their airway above water.

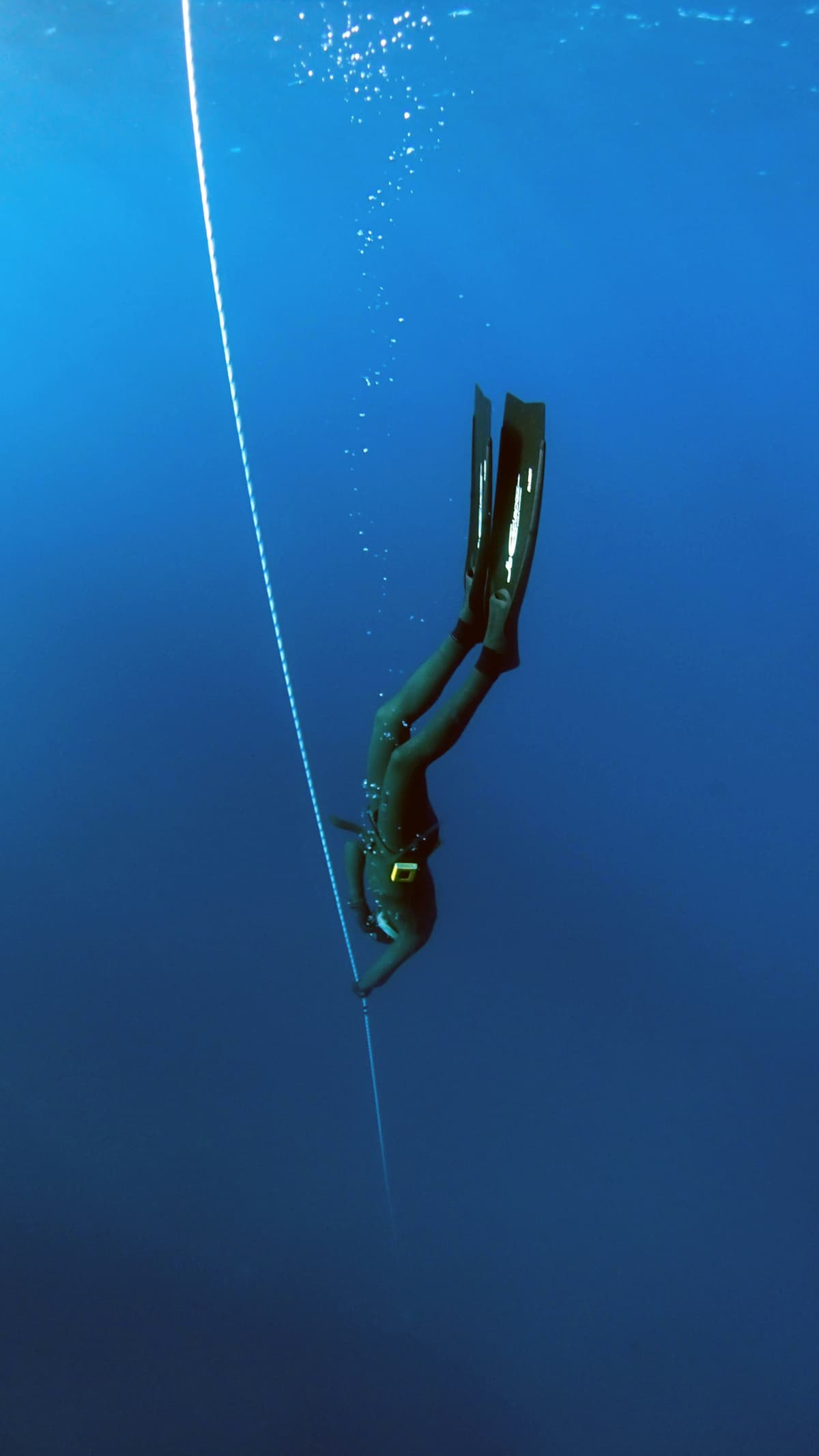

The One Up, One Down Protocol

This is the core buddy system protocol used by trained freedivers worldwide. It's simple, effective, and non-negotiable.

How It Works

One diver is always at the surface while the other is underwater. You never breath-hold at the same time.

The surface diver watches constantly. No distractions — no phone, no adjusting equipment, no chatting with others.

Meet your buddy at 10 metres depth. As your buddy ascends through the final 10 metres (the danger zone where most blackouts occur), you should be in the water, descending to meet them and escort them to the surface.

Watch their face. On the way up, position yourself to see your buddy's face. Watch for signs of hypoxia: eyes rolling, head dropping, loss of coordination.

Confirm consciousness at the surface. Within 3 seconds of surfacing, your buddy should make eye contact and give the "OK" signal. No response = immediate intervention.

Continue watching for 30+ seconds. Hypoxic symptoms can appear after surfacing. Don't relax your vigilance until your buddy has been breathing normally for at least 30 seconds.

Signs of Hypoxia to Watch For

Diver stops swimming for no apparent reason

Body goes limp or begins to sink

Head falls forward

Eyes roll back or close

Twitching or spasms (LMC/samba)

Large bubbles released from the mouth — "big bubbles mean big trouble"

At surface: confusion, inability to respond, failure to give OK signal

Rescue Procedures Every Freediver Must Know

Knowing these procedures could save your buddy's life. Practice them regularly until they're automatic.

Underwater Blackout Rescue

Descend immediately. Speed is critical. Don't waste time.

Secure the diver. Grip under the chin or on the mask strap to control their head position.

Keep their airway closed. Hold their mouth shut and chin tucked during ascent to prevent water aspiration.

Ascend directly. Emergency ascent rate is acceptable — drowning is the immediate threat.

Never risk your own life. If you cannot safely retrieve the diver, surface and call for help. A dead rescuer saves no one.

Surface Rescue: Tap-Blow-Talk

Once the diver is at the surface (or if blackout occurs at the surface):

Position the diver face-up. Support their head with their airway clear of the water.

Remove mask and any obstructions. Get the mask off their face immediately.

TAP: Firmly tap their cheeks and collarbone to stimulate a response.

BLOW: Blow sharply across their face — this can trigger the breathing reflex.

TALK: Speak loudly and clearly: "Breathe! You're OK! Breathe!"

If no response in 10-15 seconds: Begin rescue breathing. Call for emergency services.

Most freedivers recover from blackout within seconds when properly managed. If the diver regains consciousness, keep them out of the water and monitor them — no more diving that day. A 24-hour rest period is mandatory after any blackout or LMC.

What Makes a Good Buddy (vs a Useless One)

Not all buddies are created equal. An inattentive or untrained buddy provides a false sense of security that may actually be worse than diving alone — at least solo divers know they have no backup.

A Good Buddy Is:

Trained in rescue procedures and has practiced them recently

Physically capable of reaching your maximum dive depth and bringing you to the surface

Focused and attentive — not on their phone, not chatting, not adjusting gear

Honest about their limits and willing to call off dives if conditions aren't right

Someone you trust with your life — because that's exactly what you're doing

A Useless Buddy:

Hasn't been trained in rescue procedures

Can't dive to your depth

Gets distracted or isn't watching when you surface

Dives at the same time as you

Is only there because you asked them to come, not because they understand safety

Is your scuba diving partner underwater while you freedive above them

If your buddy doesn't meet the criteria for a good buddy, you may as well be diving alone.

When You Can't Find a Buddy

This is one of the most common excuses for solo diving: "I can't find anyone to dive with." Here's how to address it — and what to do if you truly can't.

Finding Dive Buddies

Local freediving clubs and communities: Most areas with decent diving have freediving groups. Search Facebook, Meetup, or ask at local dive shops.

Spearfishing clubs: Spearos often need buddies too. Join local spearfishing groups.

Freediving courses: Taking a course connects you with other divers at your level who also need buddies.

Online forums and apps: Platforms like Spearboard, local Facebook groups, or dedicated buddy-finding apps can connect you with divers in your area.

Become the buddy others want: Get trained in rescue, be reliable, be attentive. Good buddies attract good buddies.

If You Absolutely Must Dive Without a Trained Buddy

First, understand this clearly: there is no substitute for a trained buddy. The following measures reduce risk but do not eliminate it. If you black out alone, you will very likely die.

That said, if you genuinely cannot find a buddy and are going to dive anyway:

Drastically reduce your depth — stay at 50% or less of your normal maximum

Shorten your dive times — end dives well before you feel the urge to breathe

Use a float line and surface marker so boats can see you and you can rest at the surface

Have someone on shore or in a boat watching — even an untrained observer is better than no one

Tell someone where you're going and when you'll be back — so a search can begin if you don't return

Consider a freediver recovery vest — devices that inflate and bring you to the surface face-up if you don't reset them. These are a last resort, not a replacement for a buddy.

Honest message: if you can't find a buddy, the safest option is not to freedive that day. The ocean will still be there tomorrow.

Real Cases: Lives Saved and Lives Lost

These stories illustrate the difference a buddy makes.

Lives Saved by Buddies

At freediving competitions, blackouts happen regularly — and almost nobody dies. Why? Because safety divers are always present, trained, and ready. Competitive freedivers describe blackouts as frightening but manageable experiences: they wake up at the surface with their buddy supporting them, take a few breaths, and recover. The safety diver made the difference between a scary moment and a funeral.

One freediver competing in Cyprus experienced a blackout at 15 metres during a 100-metre free immersion attempt. She later recalled: "I completely lost it and blacked out. Fortunately I had the safety divers with me and everything was fine, it was just a short surface blackout." The safety divers met her at 30 metres, watched her ascend, and were ready when she lost consciousness.

Lives Lost Diving Alone

In Hawaii, an average of six freedivers die from blackouts annually. A beloved community member, Geoff Hunter, died after catching a Giant Trevally at 120 feet. He was experienced, fit, and had made countless similar dives. But he was alone when he blacked out on the ascent.

In Australia, Jacob Lollback — a rising surf lifesaving star who had moved to the Gold Coast to compete after 15 years of lifesaving — drowned while spearfishing. His age, fitness, and water experience puzzled the community. The common factor with so many similar deaths: he had lost contact with his buddy.

Neil Tedesco, a Victorian television fishing show presenter, drowned while free-dive training at a local gym pool in Frankston. He was practicing breath-holds in chest-deep water. The water was warm and shallow. Without proper supervision, it was still lethal.

The common thread in every one of these deaths: no trained buddy was watching.

Red Flags: When Buddy Training Falls Short

If you're taking a freediving course, the quality of buddy system training is one of the clearest indicators of overall course quality. For more on evaluating instructors, see our guide on how to evaluate a freediving instructor before booking.

Warning Signs Your Training Is Inadequate

Theoretical only: Instructor explains rescue but doesn't demonstrate

No hands-on practice: You never actually perform a simulated rescue

Rushed coverage: Buddy system gets a few minutes at the end of the course

Unrealistic scenarios: Practice only with cooperative, conscious "victims"

Downplaying risks: Instructor suggests blackouts are rare or the buddy system is "overly cautious"

Certification without competency: You receive certification without demonstrating rescue skills

Questions to Ask Before Training

How much time is dedicated to buddy system and rescue training?

Will I practice realistic rescue scenarios, including with unconscious divers?

Can you demonstrate the complete rescue sequence yourself?

What rescue training certifications do you hold?

Conclusion: Your Buddy Is Your Life Insurance

The buddy system is only as strong as the training behind it and the commitment of the divers implementing it.

The statistics are clear: solo divers die. Divers with trained, attentive buddies survive blackouts that would otherwise be fatal. Competitive freediving's near-perfect safety record proves that the buddy system works.

Your safety checklist:

Receive comprehensive, hands-on buddy training

Practice rescue procedures until they're automatic

Dive only with properly trained, committed buddies

Maintain conservative diving practices

Continue safety education throughout your diving career

If you can't find a buddy, don't dive

A properly trained and vigilant buddy is your lifeline underwater. Don't accept anything less than excellent safety education, and don't be the weak link in someone else's safety chain.

For more on freediving safety, see our guide to shallow water blackout and breathing techniques for beginners. Ready to start your freediving journey? Check out the complete guide to freediving in Melbourne.

Freediving Safety — Complete Series

- 1Is Freediving Dangerous? Risks, Statistics & How to Stay Safe

- 2Shallow Water Blackout: The Silent Killer in Freediving and Swimming

- 3Freediving Deaths: Causes, Prevention & What We Can Learn

- 4Freediving Safety: The Buddy System - Your Lifeline Underwater